Lord Byron’s Venice

Lord Byron’s Venice. Immersed in its libertine culture, he wrote some of his most iconic poetry, such as Beppo, Don Juan and Ode to Venice.

Uncover the poetic legacy of Lord Byron’s Venice, where the city’s haunting beauty and decadent charm, shaped some of his most daring literary achievements.

During his stay from 1816 to 1819, Byron produced works that redefined Romantic poetry; most notably Beppo, the early cantos of Don Juan and Ode to Venice These poems reflect Venice’s duality: its fading grandeur and vibrant sensuality, captured through Byron’s sharp wit, satirical tone, and innovative use of ottava rima.

In Beppo, Byron playfully critiques English morality through a Venetian lens, while Don Juan begun in Venice, blends epic scope with biting irony, challenging poetic conventions of the time. Ode to Venice, was a haunting symbol of lost grandeur, political decay, and the fragility of freedom

Venice wasn’t just a backdrop; it was a poetic symbol, embodying freedom, decay, and the intricacies of human longing.

Discover how Venice influenced Byron to defy traditional norms and craft a bold, irreverent, and uniquely modern style of poetry.

Biography

Main Venetian Works: Beppo – Don Juan: Cantos I–II – Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: Canto IV – Ode to Venice

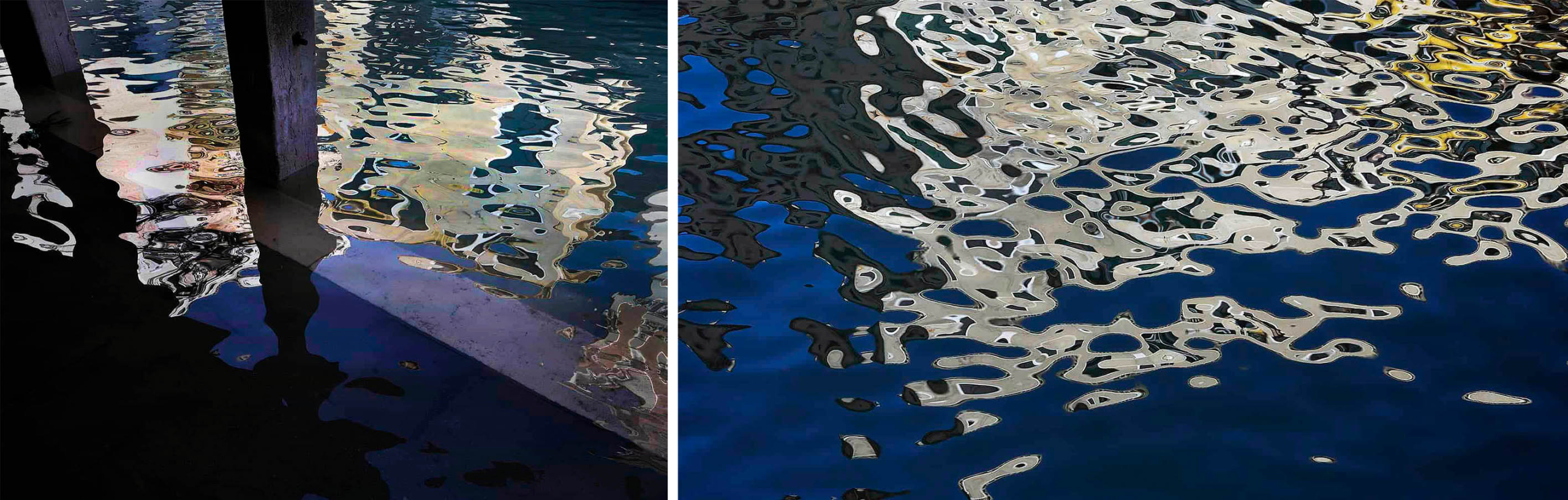

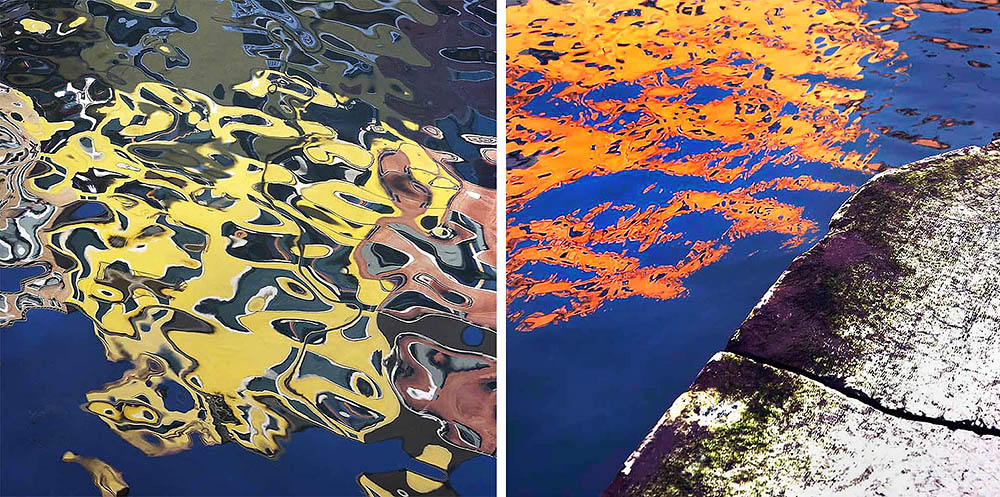

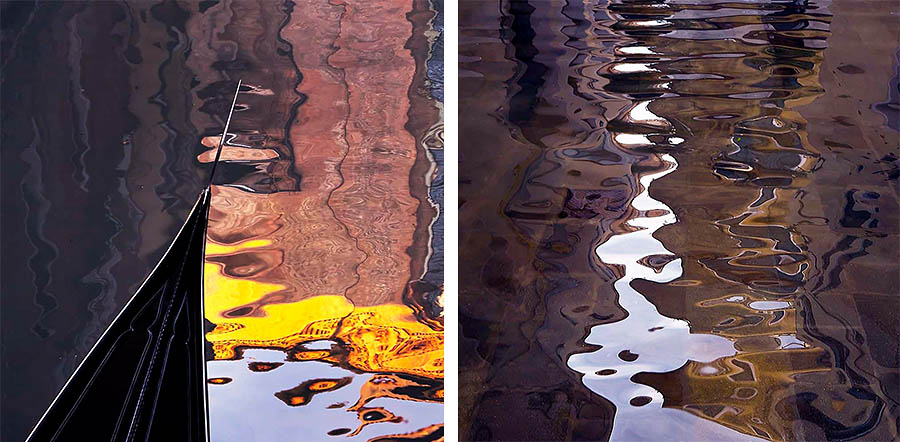

Photographic Note

Links (external–internal)

The post features images on the theme of “Water,” highlighting the interplay of light on the water’s surface, beautifully capturing Venice’s iconic charm and complementing the article’s poetic theme.

(b. January 22, 1788. London, England. – d. April 19, 1824. Messolonghi, Greece.)

‘Mad, bad and dangerous to know’. That is how Lady Caroline Lamb described her lover George Gordon Noel, sixth Baron Byron and one of the greatest Romantic poets in English literature.

Biography Lord Byron’s Venice

George Gordon Byron, sixth Lord Byron, was one of the most important poets of the British romantic period and one of the most prominent public figures in Regency England. His poetry is wide-ranging and accomplished, from lyrics and couplet satires to narrative poems and plays and the masterful satirical epic Don Juan. His life was often controversial and unconventional, and the whiff of scandal surrounding him was part of his appeal to his first admirers as well as to subsequent readers.

Born in 1788 in London, the son of Captain John “Mad Jack” Byron, who died in Byron’s infancy, Byron moved with his mother, Catherine Byron (née Gordon), to Aberdeen until, aged ten, he inherited the title of Baron Byron of Rochdale when his uncle (the “Wicked Lord Byron”) died without a legitimate male heir. Byron was educated at Harrow School and Cambridge, where he reportedly kept a bear in his rooms.

He traveled widely in Portugal, Spain, Greece, and Albania in 1809–1811 and wrote about his experiences in his first major poem, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812). This poem and the series of verse tales that followed it made Byron a celebrity in Regency society.

In 1815 he married Annabella Milbanke, and soon after the couple had a daughter, Ada. The marriage rapidly and acrimoniously deteriorated, however, and they separated in 1816. Byron would never see his daughter again. Amid rumors that some dark transgression on his part had precipitated the separation -modern scholars disagree about whether the cause lay in adultery, homosexuality, incest with his half sister Augusta Leigh, or some more prosaic explanation. Byron was ostracized from English society and left the country in 1816, never to return.

He settled in Switzerland and then in Venice, where he lived in Venice for three years, from 1816 to 1819 and became one of the legends of the city, with his palace accommodation on the Grand Canal, his great swimming feats and his notorious love-life.

More importantly, these three years were a turning point in his creative career. Venice, the fabric of which was in sad decline during Byron’s stay, was the subject of a number of serious poems, such as “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” and the “Ode to Venice” and its history provided the theme for two major dramas.

However, Byron also composed one of the wittiest and most amusing works ever written on Venetian life, with his social satire, “Beppo”. For it was in Venice that he discovered the potentialities of the Italian form of “ottava rima”, which gave him a way forward for his own poetry. His greatest poem, Don Juan, was begun in Venice and can be said to be fully Venetian in inspiration and atmosphere; even if it does not mention the city.

In Venice, he finally began the most stable and rewarding sexual relationship of his life with Theresa, wife of Count Guiciolli. After leaving Venice with the Countess, he furthered his relationship with Italy, moving to the cities of Ravenna (1819 to 1821), Pisa ( (1821-22) and Genoa (1822-1823). After spending eight years of his life in italy, he finally left for Greece in July 1823. Byron had long been a supporter of Greek independence from Turkish rule, and took an active part in the Greek struggle. He died at Messolonghi on 19 April 1824 as a result of a fever and the incompetence of his doctors. His body was returned to England.

His body was brought back to England, but the clergy refused to bury him at Westminster Abbey, as was the custom for individuals of great stature. Instead, he was buried in the family vault near Newstead. In 1969, a memorial to Byron was finally placed on the floor of Westminster Abbey.

Byron’s was a poetic, idealised image of Italy, however his depiction of his travels through the country, provides a fascinating insight into the ways that the British saw Italy and also the ways that the literature of both countries intertwined.

(NOTE.The Napoleonic Wars, had kept the English away from the European continent for nearly two decades; principally young men on their “Grand Tours” – a “rite of passage”, particularly for the wealthy and aristocratic. In 1815, Caroline of Brunswick, wife of the future King George IV; left England to buy the Nuova Villa d’Este in Cernobbio, on Lake Como. With Caroline’s purchase, Italy immediately became the height of travel fashion once again and English intellectuals, writers, artists and personalities; descended on the country. George Gordon Byron, was one of them.)

From the Riva degli Schiavoni, looking towards the southern entrance of the Grand Canal with the Salute Basilica on the left.

Main Venetian Works Lord Byron and Venice

Beppo (1817).

Lord Byron’s “Beppo”: A Satirical Venetian Tale of Love, Society, and Identity.

Venice, with its labyrinthine canals, masked balls, and fading grandeur, deeply influenced Byron’s mood and literary voice. The city’s reputation for libertinism and secrecy mirrored Byron’s own lifestyle and shaped the sensual, ironic tone of Don Juan.

Lord Byron’s Beppo: A Venetian Story, published in 1818, is a witty and satirical narrative poem that marks a stylistic shift in Byron’s poetic career. Written while engaging in a passionate affair with Marianna Segati, it is in ottava rima – a stanza form of eight lines with a rhyme scheme of ABABABCC, The poem blends humor, irony, and social commentary in a conversational tone that feels more like a lively dinner party anecdote than a solemn literary meditation. For readers unfamiliar with Byron or the poem, Beppo offers a playful yet pointed exploration of love, marriage, and cultural hypocrisy, all set against the vibrant backdrop of Venice during Carnival and deeply infused with the spirit of Venice.

At its core, Beppo tells the story of a Venetian woman named Laura whose husband, Beppo, has been missing for years, presumed dead or lost at sea. In his absence, Laura has taken a “cavalier servente,” a socially accepted lover, in accordance with Venetian custom. This arrangement, while scandalous by British standards, is portrayed by Byron as pragmatic and even affectionate. The twist arrives when Beppo returns to Venice, disguised as a Turk, having spent years in the East. Rather than erupting in fury or demanding retribution, Beppo calmly reveals his identity and reclaims his place beside Laura, who welcomes him back with surprising ease.

This seemingly simple plot serves as a vehicle for Byron’s broader critique of European society. Through the lens of Venetian customs, Byron contrasts the rigid moralism of British culture with the more relaxed, if morally ambiguous, attitudes of continental Europe. He mocks British prudery and hypocrisy, suggesting that the appearance of virtue often masks deeper failings. In Venice, Byron finds a society that embraces pleasure, tolerates human frailty, and allows for a more flexible understanding of relationships.

The poem also reflects Byron’s own experiences and worldview. Having left Britain under a cloud of scandal, Byron was living in Venice when he wrote Beppo, and the city’s cosmopolitan charm and sensuality clearly influenced his tone. The narrator frequently digresses into personal observations, offering commentary on everything from fashion to politics to poetry itself. These digressions, far from distracting, enrich the poem’s texture and reveal Byron’s delight in storytelling and satire.

Moreover, Beppo explores themes of identity and transformation. Beppo’s return as a Turk symbolizes the fluidity of cultural boundaries and the way travel can reshape one’s sense of self. Byron uses this motif to challenge fixed notions of nationality and morality, suggesting that identity is not static but shaped by experience and context.

In summary, Beppo is more than a tale of marital reunion, it is a sparkling satire that skewers societal norms, celebrates cultural diversity, and revels in the complexities of human relationships. For readers new to Byron, it offers a delightful entry point into his world: irreverent, intelligent, and always entertaining in style..

In some respect. it was Byron’s warm-up act – a witty, Venetian sketch that allowed him to test the waters of satire, irony, and narrative freedom. Don Juan took that foundation and built a sprawling, audacious epic.

Themes with Relevant Quotes

1. Satire of Love, Marriage, and Infidelity

Byron presents infidelity not as scandalous, but as a socially accepted norm in Venice. The “cavalier servente” system, where married women had official lovers; is treated with amused detachment.

“Tis an old custom of the country still, / To marry for interest and break it for whim.” – Stanza 44. This line mocks the transactional nature of marriage and the casual attitude toward extramarital affairs.

“She had her husband, and the Count had her.” – Stanza 38. A blunt, humorous summary of Laura’s situation – Byron strips away romantic pretense to show the practical reality.

2. Social Hypocrisy and Cultural Relativism

Byron contrasts English moral rigidity with Venetian permissiveness, often to the latter’s advantage.

“I like the women too (forgive my folly), / From the rich peasant-cheek of ruddy bronze, / And large black eyes that flash on you a volley / Of rays that say a thousand things at once.” – Stanza 20. Here, Byron praises Venetian women for their vitality and openness, subtly critiquing the repressed demeanor of English women.

“I love the language, that soft bastard Latin, / Which melts like kisses from a female mouth.” – Stanza 21. A sensual tribute to Italian culture, suggesting that even the language embodies warmth and pleasure.

3. Appearance vs Reality (Carnival and Masks)

Set during Carnival, the poem uses disguise as a metaphor for social roles and hidden truths.

“And thus they wore their masks, and did no harm.” – Stanza 36 Byron implies that behind the masks, people are more honest, or at least more harmless; than in societies that pretend to moral purity.

4. Cosmopolitanism and Identity

Beppo’s return as a Turk reflects Venice’s role as a cultural crossroads and the fluidity of identity.

“He was a Turk, the colour of mahogany; / And Laura saw him, and he saw Laura.” – Stanza 57 The exot*cism of Beppo’s transformation underscores Venice’s openness to other cultures and Byron’s fascination with the East.

“Venice, the only city where the marriage vow / Is not considered sacred.” – Stanza 43 A provocative line that encapsulates Byron’s view of Venetian morality: flexible, pragmatic, and unburdened by hypocrisy.

How Beppo Laid the Groundwork for Don Juan

1. Shift to Ottava Rima and Digressive Satire

Beppo was Byron’s first experiment with ottava rima, a stanza form of eight lines with an ABABABCC rhyme scheme. This form allowed Byron to blend narrative with witty digressions, ironic commentary, and sudden tonal shifts – a style he perfected in Don Juan.

“I rattle on exactly as I’d talk / Without a thought or care of what I say.” – Beppo, Stanza 81 This self-aware, conversational tone becomes the hallmark of Don Juan, where the narrator is as much a character as Juan himself.

2. Venetian Setting and Moral Ambiguity

Both poems are steeped in the Venetian ethos, a city of masks, sensuality, and moral flexibility. In Beppo, Byron introduces the cavalier servente system, where married women had socially accepted lovers. This theme of pragmatic infidelity resurfaces in Don Juan through characters like Donna Julia and Haidée.

“Venice, the only city where the marriage vow / Is not considered sacred.” – Beppo, Stanza 43. This line sets the tone for Don Juan’s irreverent treatment of love and marriage.

3. Narrator as Ironist and Philosopher

In Beppo, Byron’s narrator frequently breaks the fourth wall, digresses into philosophical musings, and mocks literary conventions. This narrative voice becomes central to Don Juan, where Byron uses irony to critique everything from politics to poetry.

“All are inclined to believe what they desire; / And I am no exception to the rule.” – Beppo, Stanza 76 This kind of self-reflective irony becomes a structural device in Don Juan.

Byron’s Personal Letters from Venice: Life Bleeding into Verse

Byron’s letters from Venice (1816–1819) reveal a man both enchanted and disillusioned. He was involved in multiple affairs, most notably with Marianna Segati, a married woman, mirroring the plot of Beppo. His observations of Venetian society, Carnival, and masked balls directly informed his poetic settings.

In a letter to his publisher John Murray (January 1818), Byron wrote:

“Beppo is a Venetian story, and written in Venice. It is meant to be light and humorous… I have taken a new tone.”

This “new tone” was the beginning of Byron’s comic realism, where he fused personal experience with literary satire.

Another letter from Venice (1818) reflects his view of the city:

“Venice is like a faded beauty – still lovely, but worn. The morals are lax, the manners polished, and the women – well, they are not English.”

This sentiment echoes in Don Juan’s treatment of European cultures, where Byron contrasts English prudery with Continental permissiveness.

Don Juan (Cantos I–II)

Lord Byron’s Don Juan consists of 16 completed cantos, with a 17th left unfinished when he died in 1824, giving a fascinating glimpse of where the tale could have headed if he had lived longer. He began writing the poem in 1818 and continued working on it throughout his life, crafting a sprawling satirical epic that remains one of his most celebrated works. Don Juan is exiled from Spain due to his scandalous affair with Donna Julia, he embarks on a series of adventures that take him across several countries and regions – Greece, Turkey, Russia and finally England. Byron uses each location not just as a backdrop, but as a lens through which to critique politics, morality, and cultural norms. The journey is less about geography and more about exposing the absurdities of human behavior across borders.

According to Byron’s manuscript records, Canto I was completed and fair-copied in Venice on September 16, 1818. Canto II was also written during his Venetian stay, though likely finished slightly later, still within his time in the city. Byron adopted the Italian stanza form ottava rima, which allowed him to blend wit, irony, and narrative fluidity.

The first two cantos of Don Juan mark the beginning of one of the most audacious and entertaining epics in English literature. Byron takes the infamous Spanish seducer Don Juan, a figure long associated with calculated debauchery,and flips the legend on its head. In Byron’s hands, Juan is not the predator but the prey: a handsome, impressionable youth who stumbles into romantic entanglements more by accident than design.

Venice wasn’t just a backdrop it was a muse. Byron’s immersion in its libertine culture and decaying grandeur deeply shaped the tone and themes of these cantos. His experiences with Venetian society, especially its romantic entanglements and moral contradictions, are mirrored in the poem’s satirical treatment of love, hypocrisy, and desire. His Venetian experiences inspired the poem’s blend of romantic escapism and cynical realism. The narrator’s voice is playful yet world-weary, much like Byron himself during this period.

Byron’s narrator often digresses into philosophical musings, echoing Schopenhauer’s ideas of will and reason. Juan and Julia represent human striving, while the narrator embodies ironic detachment. The poem becomes a kind of “Schopenhauerian epic,” where desire drives action, and reason merely comments from the sidelines.

Canto I introduces Don Juan as a young man growing up in Seville under the watchful eye of his mother, Donna Inez, a woman of formidable intellect and moral rigidity. She designs an elaborate education to shield Juan from vice, but her efforts backfire. At sixteen, Juan falls into a passionate affair with Donna Julia, a married woman whose own repressed desires erupt in a moment of moonlit surrender. Their romance is discovered, and Juan is sent away, exiled from Spain to preserve his reputation.

Canto II follows Juan’s journey at sea, where he is shipwrecked and cast adrift. He washes ashore on a remote island and is rescued by Haidée, the daughter of a pirate. In this exo*ic setting, Juan experiences a more innocent and idyllic love, free from the constraints of European society. But even this paradise is short-lived: Haidée’s father returns, and the lovers are torn apart, thrusting Juan into further adventures.

These cantos are not merely narrative episodes, they are vehicles for Byron’s sharp wit and social critique. Through digressive commentary, Byron mocks British prudery, romantic idealism, and poetic convention. His narrator is chatty, self-aware, and often irreverent, turning the poem into a kind of ongoing conversation with the reader. The use of ottava rima – an Italian stanza form with a punchy final couplet, allows Byron to shift effortlessly between elegance and comedy.

Ultimately, Cantos I and II of Don Juan are a playful yet pointed exploration of youth, desire, and the absurdities of social norms. Byron’s Venice, with its sensuality and freedom, provides the perfect backdrop for this literary reinvention. For readers new to Byron, these cantos offer a dazzling introduction to his genius: bold, subversive, and irresistibly entertaining.

Major Themes

1. Satire of Love and Marriage

Byron mocks the institution of marriage, portraying it as rife with hypocrisy and dissatisfaction: Donna Inez and Don José’s dysfunctional relationship is a prime example: “She kept a journal, where his faults were noted.”

Donna Inez and Don José, are portrayed earlier in the canto as a mismatched and dysfunctional couple. Their relationship is marked by cold calculation and mutual disdain, not romantic passion. Byron uses them to satirize the institution of marriage

Donna Julia’s affair with young Juan exposes the double standards of society: “A real husband always is suspicious.”

Donna Julia married to Don Alfonso, finally gives in to her feelings for the young Don Juan. Byron captures the tension between moral resistance and passionate surrender with that famously ironic line. Julia had been struggling with her conscience, trying to resist temptation, but ultimately succumbs. Byron uses them as vehicle for exploring desire and hypocrisy. Byron critiques societal norms that punish women more harshly than men for infidelity, highlighting the gendered moral codes of his time.

2. Hypocrisy and Social Pretension

Characters often present a virtuous facade while engaging in morally questionable behavior. Byron exposes this duplicity with biting wit: Donna Julia is seen as “pure and religious,” yet secretly pursues Juan. Don Alfonso, though jealous and controlling, is not above suspicion himself.

“Let us have wine and women, mirth and laughter, / Sermons and soda-water the day after.” This line mocks the moral duplicity of society—indulgence followed by performative repentance. Byron exposes how people sin freely, then seek absolution through superficial gestures.

“What, after all, are all things — but a show?” A direct jab at the performative nature of social life. Byron suggests that much of what society values: status, virtue, decorum; is mere spectacle.

3.The Journey and transformation.

Canto II shifts to a more adventurous tone, as Juan survives a shipwreck and lands on a Greek island.

“Then rose from sea to sky the wild farewell— Then shriek’d the timid, and stood still the brave,— Then some leap’d overboard with fearful yell, As eager to anticipate their grave.” This stanza captures the chaos and terror of the shipwreck, contrasting courage and panic in Byron’s signature sardonic tone. This marks the beginning of his transformation from naïve youth to worldly wanderer, a motif that continues throughout the epic.

4. Quote Reflecting Venetian Decadence:

“But passion most dissembles, yet betrays / Even by its darkness; as the blackest sky / Foretells the heaviest tempest.” This line captures the tension between outward restraint and inner turmoil, a theme that resonates with Venice’s veiled sensuality.

5. Philosophical Undertones

Byron’s narrator often digresses into philosophical musings, echoing Schopenhauer’s ideas of will and reason. Juan and Julia represent human striving, while the narrator embodies ironic detachment. The poem becomes a kind of “Schopenhauerian epic,” where desire drives action, and reason merely comments from the sidelines

Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: Canto IV

A Poetic Farewell to Glory, Memory, and Self

Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage consists of four cantos, published between 1812 and 1818. Each canto follows the travels and reflections of the titular character, Childe Harold, a melancholic, world-weary young man seeking meaning in foreign lands. (Note: the term “childe” refers to a medieval title for a noble young man preparing for knighthood.)

Written in Venice and published in 1818, Canto IV of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage is one of Lord Byron’s most introspective and majestic works. Unlike the earlier cantos, which follow the fictional Harold, this final canto largely abandons the character and speaks in Byron’s own voice. It is a sweeping meditation on history, art, nature, and the transience of human ambition, composed as Byron wandered through Italy’s ruins and reflected on both personal and political loss. Childe Harold inaugurated the literary archetype of the “Byronic hero,” a darkly glamorous figure, reminiscent of Lord Byron himself, and later iterated in several of his other works – characterized by his charisma, moodiness, and mysterious past.

The canto opens with Byron’s haunting vision of Venice, the city where he wrote much of the poem. Once a mighty republic, Venice is now a faded relic of its former glory. Byron captures this duality in one of the canto’s most famous lines: “I stood in Venice, on the Bridge of Sighs; / A palace and a prison on each hand.” This image sets the tone for the poem’s central theme – civilizations rise and fall, leaving behind beauty tinged with sorrow.

Byron’s journey then moves through other Italian cities – Arqua, Ferrara, Florence, and Rome,each evoking reflections on art, mortality, and the endurance of imagination. In Florence, he marvels at the legacy of Renaissance genius, writing: “States fall, arts fade—but Nature doth not die, / Nor yet forget how Venice once was dear.” Here, Byron contrasts the decay of political power with the timelessness of nature and the enduring spirit of artistic creation.

Rome becomes the emotional and philosophical climax of the canto. As Byron walks among its ruins, he contemplates the rise and fall of empires and the vanity of human ambition. He calls Rome: “The Niobe of nations! there she stands, / Childless and crownless, in her voiceless woe.” This metaphor evokes a city frozen in grief, once glorious, now silent, a powerful symbol of historical decline.

Yet amid this melancholy, Byron finds solace in nature and solitude. In one of the most quoted stanzas of the entire poem, he writes: “There is a pleasure in the pathless woods, / There is a rapture on the lonely shore, / There is society where none intrudes, / By the deep Sea, and music in its roar.” This passage reveals Byron’s yearning to escape the corruption of society and immerse himself in the purity of the natural world.

The sea itself becomes a symbol of eternal power and mystery. Byron exclaims: “Roll on, thou deep and dark blue Ocean—roll! / Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain.” Here, the ocean mocks human pride and conquest, reminding us that nature endures while empires vanish.

Throughout Canto IV, Byron’s voice is deeply personal. He reflects on his exile from England, the death of his daughter, and the disillusionment of fame. He writes: “And what is writ, is writ— / Would it were worthier! but I am not now / That which I have been.” This confession reveals a man grappling with change, loss, and the passage of time.

In summary, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage: Canto IV is a poetic farewell, not just to Harold, but to youth, illusion, and worldly glory. For those new to Byron, it offers a masterclass in lyrical reflection, where the ruins of Italy become mirrors for the poet’s own inner landscape. It is a work of sublime melancholy and philosophical depth, where history, nature, and personal sorrow converge in verse that still resonates today.

Further Themes:

Each of these themes contributes to the poem’s rich emotional and intellectual landscape. Byron isn’t just chronicling a journey through Italy, he’s mapping the ruins of the human spirit, and searching for meaning in what remains.

1. The Passage of Time.

Byron is obsessed with how time erodes even the greatest achievements. Cities like Venice and Rome are monuments to past glory, now crumbling under the weight of history.

He writes: “There is the moral of all human tales; / ’Tis but the same rehearsal of the past.” This line captures his belief that history repeats itself, and that human pride is ultimately humbled by time.

2. Art as Immortality.

While empires fall, Byron sees art and poetry as enduring. He visits the tombs of Petrarch and Tasso, reflecting on how their words outlasted their nations. Art becomes a kind of defiance against oblivion.

“The poetry of earth is never dead.” Though this line is Keats’s, Byron echoes the sentiment – art preserves beauty and emotion beyond the reach of decay.

3. Nature’s Sublimity.

Nature is Byron’s refuge. Unlike human constructs, it is eternal, powerful, and indifferent to politics. His apostrophe to the ocean is one of the most famous in English literature:

“Roll on, thou deep and dark blue Ocean—roll!” The sea represents freedom, mystery, and the sublime – a force that humbles human ambition.

4. Spiritual and Philosophical Reflection.

Byron isn’t just sightseeing, he’s soul-searching. The ruins prompt existential questions about mortality, legacy, and the futility of conquest. He often turns inward, asking what truly matters when all else fades.

5. Political Disillusionment.

Byron critiques tyranny and the abuse of power, especially in his reflections on Rome. He’s disillusioned with political systems that promise greatness but deliver suffering. His tone is often bitter when discussing rulers and empires.

6. Isolation and Emotional Exile.

Though surrounded by beauty, Byron feels profoundly alone. His personal grief, especially over the loss of his daughter and his estrangement from England; haunts the canto. The ruins, mirror his inner desolation.

ODE TO VENICE

Lord Byron’s “Ode on Venice” is a powerful lament for the decline of a once-great city and, more broadly, for the decay of freedom and the rise of tyranny across Europe. It is a strong example of his ability to blend historical lament with poetic intensity.

Written in 1818 and published with Mazeppa in 1819, the poem is steeped in sorrow and indignation, painting a vivid picture of Venice’s fallen state and contrasting it with its glorious past. The tone is initially mournful, evolving into a passionate call for resistance against oppressive forces. There is a shift from mourning Venice and its lost glory to a condemnation of tyranny and a plea for the preservation of freedom.

“Ode on Venice” is more than just a lament for a fallen city; it is a powerful meditation on the nature of freedom, the burden of history, and the ever-present threat of tyranny.

Byron’s passionate language and vivid imagery create a lasting impression of Venice’s decline and a sense of urgency about the need to defend liberty. The poem serves as a timeless reminder that freedom is not guaranteed but must be constantly fought for and cherished.

The poem’s enduring relevance lies in its ability to resonate with readers who have witnessed the rise and fall of nations and the ongoing struggle for human rights.

The opening lines, evoking a future where Venice is lost beneath the sea: “Oh Venice! Venice! when thy marble walls / Are level with the waters, there shall be / A cry of nations o’er thy sunken halls”.

Main Themes and Quotes

1. The Decay of a Glorious Past

Byron laments the fall of Venice from its historic grandeur to a state of stagnation and ruin.

“Thirteen hundred years / Of wealth and glory turn’d to dust and tears” This line captures the weight of history and the tragedy of its loss. Venice’s long legacy is reduced to sorrow and decay.

“Church, palace, pillar, as a mourner greets” Even the architecture becomes a symbol of grief, as if the city itself mourns its faded glory.

2. The Loss of Freedom and Rise of Tyranny

Venice, once a beacon of republican liberty, is now subdued under foreign rule – a metaphor for the broader decline of freedom in Europe.

“And the harsh sound of the barbarian drum… repeats / The echo of thy tyrant’s voice”. Byron evokes the oppressive presence of foreign powers, replacing the musical vibrancy of Venice with the dull thud of domination.

“Pour your blood for kings as water”. A scathing indictment of blind loyalty to monarchs, urging resistance against tyranny.

3. Stagnation and Apathy

The Venetians are portrayed as passive and diminished, unable to reclaim their former spirit.

“Crouching and crab-like, through their sapping streets”. This image suggests a people who have lost their vitality, creeping through a decaying city.

“And yet they only murmur in their sleep”. Rather than rising in protest, the citizens are depicted as sleepwalking through their decline.

4. Hope and the Call to Resistance

Despite its mournful tone, the poem ends with a glimmer of hope – especially in Byron’s praise of America as a symbol of enduring liberty.

“America is presented as a beacon of hope”. Though not a direct quote, Byron contrasts the decay of Europe with the promise of freedom in the New World.

“Better, though each man’s life-blood were a river, That it should flow, and overflow, than creep Through thousand lazy channels in our veins Damm’d like the dull canal with locks and chains…”. This symbolic contrast urges active resistance over passive submission.

How does the structure of the poem, play a crucial role in shaping its emotional impact and thematic depth?

In essence, the structure of Ode on Venice isn’t just a vessel for Byron’s ideas, it’s part of the message. The formal elegance contrasts with the city’s ruin, underscoring the tragedy of a civilization that once harmonized art, liberty, and power.

1. Stanzaic Form and Rhythm.

The poem is composed in regular stanzas, often using iambic pentameter, which gives it a steady, solemn rhythm – mirroring the mournful tone of the elegy.

- This measured pace reflects the weight of history and the slow decay of Venice.

- The regularity also contrasts with the chaos and decline Byron describes, emphasizing the tragedy through poetic control.

2. Classical Ode Structure.

As an ode, the poem follows a traditional tripartite structure.

- Strophe: Introduces the subject – Venice’s faded glory.

- Antistrophe: Offers a counterpoint – its current degradation and foreign domination.

- Epode: Concludes with reflection or resolution – often a call to liberty or a lament.

This classical form elevates venice to mythic status, reinforcing Byron’s reverence for its past and sorrow for its fall.

3. Juxtaposition and Contrast.

Byron frequently contrasts:

- Past vs. Present: “Thirteen hundred years / Of wealth and glory turn’d to dust and tears”

- Freedom vs. Tyranny: “The harsh sound of the barbarian drum… repeats / The echo of thy tyrant’s voice”

These structural juxtapositions intensify the emotional resonance and highlight the central theme of lost liberty.

4. Direct Address and Apostrophe.

Byron speaks directly to Venice as if it were a living entity: “Oh Venice! Venice! when thy marble walls / Are level with the dust...”

This rhetorical device creates intimacy and urgency, making the reader feel the poet’s grief and admiration more personally.

5. Flow and Musicality.

The poem’s structure allows Byron to weave lyrical passages with political critique, maintaining a balance between beauty and bitterness. The musicality of the verse evokes the lost songs of Venice, now replaced by silence or foreign drums.

“Last light over San Giorgio Maggiore”

LINKS (external–internal)

Byron in Italy Essential reading together with this post above. As famous for his notorious private life as for his poetry, this very comprehensive and illustrated post describes his eventful life in Italy, including his threee-year stay in Venice. Byron became one of the legends of the city, with his palace accommodation on the Grand Canal, his great swimming feats and his notorious love-life.

In this developing series in the category of “The Literature of Venice”, we dive deeper into literary works about Venice; focusing on how each chosen author tackles common themes, and highlighting their most illuminating quotes about the city.

The Literature of Venice (Introduction)

Henry James and the Allure of Venice

Death in Venice by Thomas Mann

Ernest Hemingway’s Love for Venice

See my unique “Depicting Venice” series of composite images and learn how they were conceived and made. The are several ways to order the images into a block. The fascination is in its unpredictability.

“Depicting Venice – Ian Coulling”

Photographing Venice – Transforming decaying walls into art.

Venice – Great Poetry and Images

You Tube Video 15 min: The Scandalous Life of a Genius – Lord Byron

You Tube Video 58 min: Lord Byron: Mad, Bad & Dangerous To Know | Part 1