Ezra Pound’s Venice

Ezra Pound’s Venice. Explore the connection between the modernist poet and the city that would shape his artistic and spiritual journey.

From his early visits and first published works to his final years spent in quiet reflection, Venice played a central role in shaping Ezra Pound’s poetic vision and legacy.

This insightful blog post delves into how the city’s rich history, art, and architecture inspired The Cantos and other works, offering readers a unique perspective on 20th-century literature, literary travel, and the cultural impact of one of modernism’s most controversial figures.

BiographyVenetian WorksKey Themes, Motifs and Quotations.Photographic NoteLinks (external-internal)

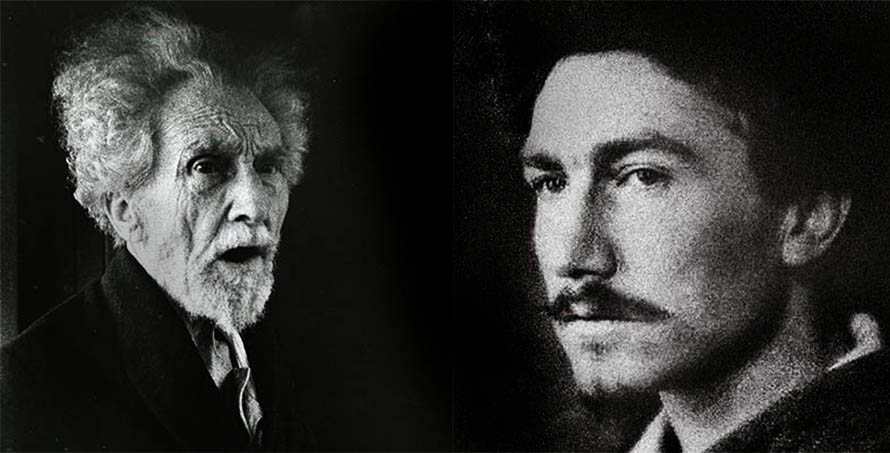

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (b. 30 October 1885, Hailey, Idaho, USA – d. November 1972, Venice, Italy)

Biography

Ezra Pound was born to federal land office official Homer Loomis Pound and Isabel Weston. His family moved east in 1887, settling near Philadelphia, where he attended Cheltenham Military Academy and the University of Pennsylvania, earning an MA after a bachelor’s degree in philosophy from Hamilton College in 1905.

After relocating to London, he emerged in the 1910s as a driving force behind Imagism, advocating clarity, precision, and economy of language; editing the first anthology “Des Imagistes” in 1914. Under his editorial guidance, he helped refine the voices of literary giants such as T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, and Hilda Doolittle (who wrote under the initials H.D); yet his own legacy remains shadowed by political infamy and personal contradictions.

Among the many cities that marked his life, Venice stands out not merely as a place of residence or inspiration, but as a poetic and spiritual axis – a city that mirrored his aesthetic ambitions and internal complexities.

Pound’s relationship with Venice began early. In 1898, at the age of twelve, he visited the city with his Aunt Frank, an experience that left a lasting impression. A decade later, in 1908, he returned to Venice and published his first poetry collection, A Lume Spento, (“With Tapers Quenched,” referencing Dante’s Inferno), a self-financed volume that revealed his early fascination with European culture, classical allusion, and the interplay of light and decay. The title itself “With Tapers Quenched”,evokes a Venetian sensibility: the flickering of civilization, the beauty of its twilight.

Indeed, Venice permeates The Cantos, not always explicitly, but as a recurring aesthetic and philosophical presence. The city’s maritime legacy, its role in the transmission of classical knowledge, and its visual splendor all inform Pound’s epic ambition to distill the essence of civilization into verse. In poems like “San Trovaso,” he captures the quiet dignity of Venetian spaces, while his Venetian sketch-book reveals a poet attuned to the city’s textures and tonalities. Venice becomes both muse and mirror,a place of brilliance and decay, reflecting Pound’s own oscillation between visionary insight and ideological blindness.

That blindness became tragically manifest during World War II, when Pound’s support for Mussolini and fascism led to his arrest for treason in 1945. After a period of incarceration in Pisa and confinement in St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., he was released in 1958 and returned to Italy; eventually settling in Venice. In his final years, Pound lived in near silence, often seen walking the city’s bridges and canals in contemplative solitude. He died in Venice on November 1, 1972, and was buried on the island of San Michele, joining a pantheon of artists and writers who found their final repose in the city of water.

Venice in the end, was more than a setting for Ezra Pound; it was a poetic condition. Its shimmering surfaces and submerged histories echoed his lifelong quest to reconcile beauty with truth, form with meaning, and civilization with its discontents. In Venice, Pound found both refuge and reckoning, a city that embraced his genius while quietly absorbing his contradictions.

Ezra Pound died in Venice on November 1, 1972 and is interred in the Protestant section of the San Michele Cemetery in Venice; where he lies near other luminaries such as Sergei Diaghilev and Igor Stravinsk and Joseph Brodsky. A procession of four gondoliers dressed in black, had rowed his body across the Venetian lagoon to San Michele.

His legacy remains as one of the most influential and controversial figures in 20th-century literature. His innovations in poetic form, his role as a literary mentor, and his complex political legacy continue to provoke debate. Yet in Venice, his story finds a quieter echo: a city of shadows and light, of beginnings and endings, where poetry and memory linger in the stones.

Reality and Illusion-18

Venetian Works. Ezra Pound’s Venice

These are Ezra Pound’s key works in relation to Venice, with selected quotes, that reflects how the city shaped his poetic imagination, cultural ideals, and personal myth:

A Lume Spento (1908)

Ezra Pound’s A Lume Spento (1908), his self-published debut collection, is a bold and eccentric introduction to a poet already determined to defy convention. Composed in Venice and dedicated to his late friend William Brooke Smith, the volume’s title, translated as “With Tapers Quenched”; is drawn from Dante’s Purgatorio, evoking themes of spiritual exile and redemption. This allusion sets the tone for a collection steeped in literary tradition yet bristling with modernist ambition.

The forty-five poems are rich with allusions to Provençal troubadours, Victorian decadents, and classical mythology. Pound adopts dramatic monologues in the style of Robert Browning, speaking through historical and legendary personae. These voices often reflect a kind of spiritual mediumship, as if the poet were channeling the dead. In “La Fraisne,” for instance, he writes: “Love thou thy dream / All base love scorning, / Love thou the wind / And here take warning / That dreams alone can truly be”, suggesting a rejection of worldly desire in favor of visionary idealism.

Stylistically, A Lume Spento is uneven but daring. Pound’s youthful exuberance leads to moments of obscurity and affectation, yet the collection pulses with originality. In “Cino,” he declares, “Bah! I have sung women in three cities… I will sing of the sun,” signaling a shift from romantic indulgence to elemental clarity – a gesture that anticipates his later Imagist principles.

Thematically, the poems trace a Dantean arc: figures consumed by passion descend into metaphorical hells, while the poet himself aspires to transcendence. In “Scriptor Ignotus,” Pound questions his own poetic identity, yet ends with a defiant pride in his craft. The collection’s spiritual and aesthetic progression mirrors Pound’s own journey, from imitation to innovation.

Though Pound later dismissed the book’s quality, A Lume Spento remains a compelling artifact of his early vision: a fusion of medieval mysticism, modern defiance, and poetic self-invention. It is, as one early reviewer put it, “wild and haunting stuff… absolutely poetic, original, imaginative, passionate, and spiritual”.

Reality and Illusion-19.

San Trovaso Sketches (1908)

Ezra Pound’s San Trovaso Sketches, published in 1908, is drawn from his Venetian notebook, that he kept during his stay in the Dorsoduro district of Venice; overlooking the gondola workshops of Rio di San Trovaso. It marks an early turning point in his poetic development. district of Venice, The fifteen poems in a slim volume, reflect a deep emotional and aesthetic engagement with the city’s beauty and mystery. Venice becomes more than a backdrop – it’s a spiritual force, evoked through shadowy canals, sacred architecture, and a sense of romantic melancholy.

As Pound writes in “Night Litany,” “Thou art as a priestess, oh holy shadow of thy handmaid,” casting the city in a sacred, almost mystical light.

Pound’s style here is deliberately raw and experimental, challenging the polished verse of his Edwardian contemporaries. He sought what he called “literary barbarianism,” using archaic language and compressed imagery to forge a new poetic voice. This rebellion against tradition foreshadows the innovations of Imagism and his later modernist work. In “Scriptor Ignotus,” he declares, “I am weary of the words of the world,” signaling his desire to transcend conventional poetic language.

Themes of departure and longing run throughout the collection. In “Partenza di Venezia,” Pound likens leaving the city to parting from a beloved: “Ne’er felt I parting from a woman loved / As feel I now my going forth from thee.” This line underscores the depth of his attachment and the emotional resonance Venice held for him.

Later, in Canto LXXVI Pound writes: “My window looked out on the Squero / where Ogni Santi meets San Trovaso.” The specificity of place anchors memory and poetic reflection.

Ultimately, San Trovaso Sketches is not just a travel-inspired meditation – it’s a declaration of artistic intent; revealing a young poet already restless with convention and eager to reshape the literary landscape.

The Cantos (1915–1962)

Ezra Pound’s The Cantos (1915 – 1962) is a towering, enigmatic epic, where Venice becomes a poetic model of balance between beauty, commerce, and civic virtue, that defies conventional poetic form. Composed over nearly fifty years, it is a collage of history, myth, economics, and personal confession; a modernist cathedral built from fragments.

Pound’s ambition was vast: “I have tried to write Paradise / Do not move / Let the wind speak / that is paradise.” This haunting line from the Pisan Cantos, captures both his yearning for transcendence and the quiet humility of a poet confronting failure.

The poem opens with a descent, echoing Homer and Dante: “And then went down to the ship / Set keel to breakers, forth on the godly sea.” This invocation of Odysseus sets the tone for a journey through the underworld of Western civilization. Pound’s heroes—Confucius, Jefferson, John Adams—appear as guides or exemplars. In Canto XIII, he writes: “And Kung gave the words ‘order’ / and ‘brotherly deference’ / And said nothing of the ‘life after death.’” Here, Confucius embodies Pound’s ideal of ethical clarity without religious dogma.

Economic critique pulses through the work, especially in Canto XLV: “With usura hath no man a house of good stone / each block cut smooth and well fitting.” Usury, for Pound, is not merely financial malpractice, it is a spiritual corruption that erodes art, architecture, and human dignity. He contrasts this with praise for the Monte dei Paschi di Siena, a “damn good bank” sustained by tangible wealth: “Pine cuts the sky into three / Thus BANK of the grassland was raised.”

The Pisan Cantos, written during Pound’s imprisonment in Pisa in 1945, are among the most lyrical and introspective. In Canto LXXXI, he pleads: “Let the Gods forgive what I have made / Let those I love try to forgive what I have made.” These lines reveal a man grappling with the consequences of his political choices, seeking absolution through poetry.

Yet The Cantos is not a confession, it is a vision. In Canto CXV, he writes: “M’amour, m’amour what do I love and where are you? That I lost my center fighting the world.” This line distills the emotional core of the work: a poet torn between ideals and reality, between beauty and chaos.

Ultimately, The Cantos is a poem of ambition and fragmentation, of brilliance and contradiction. It is not meant to be read linearly, but lived through – an intellectual and emotional odyssey that challenges the reader to assemble meaning from its dazzling shards.

Reality and Illusion-20

Indiscretions, or Une Revue de Deux Mondes (1920)

Written during a 1920 stay in Venice, the city plays a subtle but evocative role in the work. Pound had a deep personal connection to the city, having first visited it as a child and later returning multiple times before settling there in his later years.

In Indiscretions, Venice emerges not just as a backdrop; but as a symbolic counterpoint to the provincialism of America and a more cosmopolitan and historical consciousness. These quotes below, help illuminate the book’s central tension: the clash between old and new worlds, between inherited values and artistic rebellion.

On cultural contrast, he writes with characteristic understatement: “Venice was an excellent place to come to from Crawfordsville, Indiana.” This understated remark encapsulates the aesthetic and intellectual relief Pound felt in escaping the American Midwest for the layered beauty of Europe.

Regarding American provincialism: “The American mind is a mind that has never been made up.” This line reflects Pound’s frustration with what he saw as the intellectual indecisiveness and cultural superficiality of his homeland.

On generational misunderstanding: “My father had the decency not to understand me.” A poignant and sardonic reflection on the emotional distance between Pound and his father, and perhaps between artists and the society that raises them.

Finally, on artistic identity: “The artist is always beginning. Any work of art which is not a beginning, an invention, a discovery is of little worth.” Though echoed in other writings, this sentiment runs through Indiscretions, underscoring Pound’s belief in perpetual reinvention.

Letters and Memoirs (1898–1972)

Letters and Memoirs is not just a record of Pound’s life – it is a chronicle of modernism’s birth, a testament to the power and peril of uncompromising genius. Through its pages, we encounter a man who shaped literary history while wrestling with its moral and political undercurrents.

His Letters and Memoirs (1898–1972) offer a vivid and often unfiltered portrait of one of the 20th century’s most controversial and brilliant literary figures. Spanning nearly the entirety of his life,from precocious youth to embattled old age; these writings reveal Pound not only as a poet but as a polemicist, mentor, and cultural provocateur. Through correspondence with figures like T.S. Eliot, James Joyce, H.D., and William Carlos Williams, we witness the forging of modernist literature in real time, shaped by Pound’s relentless energy and uncompromising vision.

The letters are often electric with conviction. In one, he declares: “Literature is news that stays news,” underscoring his belief in the enduring power of poetic language. Elsewhere, he writes with characteristic urgency: “Real education must ultimately be limited to men who insist on knowing; the rest is mere sheep-herding.” These lines reflect his disdain for intellectual complacency and his lifelong commitment to cultural reform.

Pound’s memoiristic reflections, especially those written during his confinement at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, are more introspective. In a moment of bitter clarity, he admits: “I found after seventy years that I was not a lun*tic but a moron… I should have been able to do better.” This self-assessment, tinged with regret, reveals a man grappling with the consequences of his political misjudgments and the limits of his influence.

Yet even in his later years, Pound remained fiercely devoted to the idea of artistic integrity. “The artist is always beginning,” he wrote, “Any work of art which is not a beginning, an invention, a discovery is of little worth.” This credo runs through his life’s work, from The Cantos to his editorial interventions in Eliot’s The Waste Land.

Reality and Illusion-21

Key Themes, Motifs and Quotations. Ezra Pounds Venice

Here’s the thematic breakdown of Ezra Pound’s Venetian works, now with source attributions for each quote. These lines span The Cantos, essays, letters, and speeches, offering a rich tapestry of Pound’s engagement with Venice as both a physical city and symbolic ideal.

Architecture and Light

Pound saw Venetian architecture as a fusion of visual clarity and spiritual resonance.

- “A real building is one on which the eye can light and stay lit.”Source: The Cantos (quoted in The Cantos Project) Commentary: Architecture, for Pound, must arrest and sustain attention – Venice’s façades do just that.

- “I first saw Venice in 1898 and have always wanted to go back. It has never disappointed me.” Source: Personal recollection, quoted in Kristin Cann’s thesis Ezra Pound’s City: The Total Light Process Commentary: A lifelong enchantment with Venice’s luminous beauty and architectural harmony.

- “Venetian glass… expresses the taut curvature of the cold under-sea, the slow, oppressed yet brittle curves of dimly translucent water.” Source: Canto XVII, A Draft of XXX Cantos (1930) Commentary: Light becomes tactile, captured in glass, shaped by water.

Historical Continuity and Civic Order

Venice’s layered history and civic rituals resonated with Pound’s vision of cultural coherence.

- “The temple is holy because it is not for sale.” Source: The Cantos (quoted in Goodreads and A-Z Quotes) Commentary: A rebuke of commodification – Venice’s sacred spaces embody civic sanctity.

- “Until you know who has lent what to whom, you know nothing whatever of politics, you know nothing whatever of history.” Source: Ezra Pound Speaking: Radio Speeches of World War II (1978) Commentary: Economic transparency as the bedrock of civic order.

- “When words cease to cling close to things, kingdoms fall, empires wane and diminish.” Source: A Memoir of Gaudier-Brzeska (1970) Commentary: Venice’s inscriptions and poetic echoes preserve this vital linguistic connection.

Decay and Vitality

Venice’s faded grandeur mirrored Pound’s tension between cultural decline and renewal.

- “If a nation’s literature declines, the nation atrophies and decays.” Source: ABC of Reading (1934) Commentary: Venice’s literary echoes—from Petrarch to Brodsky—stand against cultural erosion.

- “A classic is classic… because of a certain eternal and irrepressible freshness.” Source: ABC of Reading (1934) Commentary: Even amid decay, vitality persists through artistic renewal.

- “We do NOT know the past in chronological sequence… what we know we know by ripples and spirals eddying out from us.” Source: Guide to Kulchur (1938) Commentary: History in Venice is tidal—layered and nonlinear.

Poetic Pilgrimage and Personal Myth

Venice was both a literal and symbolic endpoint in Pound’s poetic journey.

- “I have tried to write Paradise… Let the wind speak that is paradise.” Source: The Pisan Cantos (1948) Commentary: Venice’s winds and canals become metaphors for poetic transcendence.

- “Our life is… made up in great part of things indefinite, impalpable… it is precisely because the arts present us these things that we… cannot get on without the arts.” Source: I Gather the Limbs of Osiris (1911) Commentary: Venice’s intangible beauty is best captured through art.

- “The Cantos are the story of active man… searching for his city.” Source: Kristin Cann’s thesis Ezra Pound’s City: The Total Light Process Commentary: Venice as poetic axis—both destination and mythic ideal.

Commerce and Ethics

Pound’s critique of financial exploitation finds a potent backdrop in Venice’s mercantile legacy.

- “USURY is the cancer of the world, which only the surgeon’s knife of Fascism can cut out.” Source: Ezra Pound Speaking: Radio Speeches of World War II (1978) Commentary: A controversial stance, linking ethical commerce to cultural health.

- “Wars in old times were made to get slaves. The modern implement of imposing slavery is debt.” Source: Ezra Pound Speaking (1978) Commentary: Venice’s historical wealth prompts reflection on the moral cost of trade.

-

“The temple is holy because it is not for sale.” Source: The Cantos (repeated for emphasis). Commentary: A line that bridges civic ethics and economic critique.

Reality and Illusion-21 (composite of 16 identical images)

Photographic Note

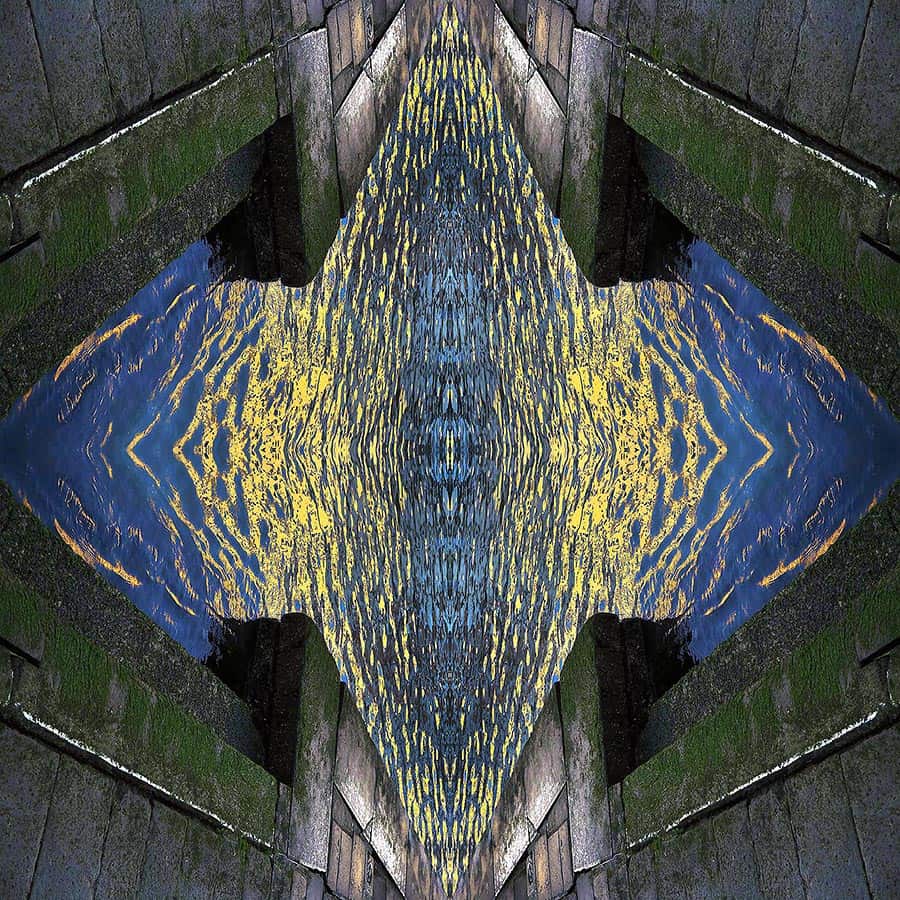

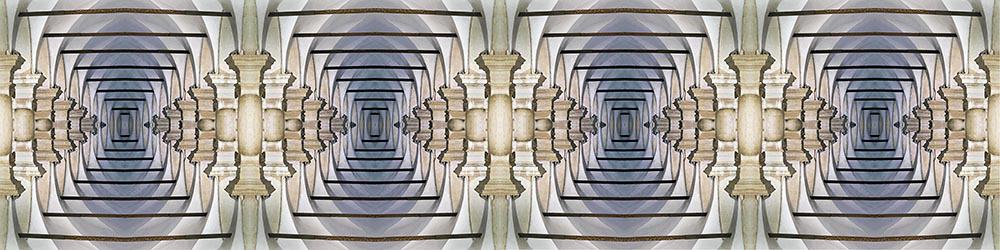

In the imagery presented in this post and his three others linked below, Ian Coulling creates a new visualisation of the Venetian urban landscape. A single original photograph, together with three other horizontally and vertically reversed images; were combined to form a new composite. Photographs were selected for showing how direct and reflected light, acts at the interface of air and water; to produce the magic, of “reality and illusion”, or in other terms “solidity and liquidity”. Others were chosen, capturing reflected light only, giving a more abstracted effect (no 20 and 21 above).

In these composites, a whole new Venetian world opens up and strange image components appear; such as new and rather “fantastical” structures and often biomorphic forms. The whole is greater than the sum of its parts. They are best viewed online at a large image size, so that you can really look into and explore the new visual world created.

The inspiration to investigate the potential of the composite image-making process, to explore the effects of multiple image planes, altered perspectives and space in Venetian urban scenes; essentially came from quotes made by artists, writers and poets over the centuries; regarding the “floating nature of Venice, its magical direct and reflected light and its mirror effects”.

LINKS (external–internal)

In this developing series in the category of “The Literature of Venice”, we dive deeper into literary works about Venice; focusing on how each chosen author tackles common themes, and highlighting their most illuminating quotes about the city.

The Literature of Venice (Introduction)

Henry James and the Allure of Venice

Death in Venice by Thomas Mann

Ernest Hemingway’s Love for Venice

See my unique “Depicting Venice” series of composite images and learn how they were conceived and made. The are several ways to order the images into a block. The fascination is in its unpredictability.

“Depicting Venice – Ian Coulling”

Photographing Venice – Transforming decaying walls into art.

Venice – Great Poetry and Images

19 MINS. You Tube VIDEO: Ezra Pound documentary

Ezra Pound’s Venice Ezra Pound’s Venice Ezra Pound’s Venice Ezra Pound’s Venice Ezra Pound’s Venice